Fiction invites us to experience other peoples’ lives. As writers and readers, we enter territories—geographic, physical, psychic—that would not otherwise be available to us. A believable character is a guide to another world. For the masterful writer and the fortunate reader, “real” characters inhabit lives of their own that extend past the time of writing and reading.

As writers, we know and invent more about our characters than we show or tell. We can develop histories, physical descriptions, and emotional baggage for our characters through lists, biographies, interviews, photos, scrapbooks. (More on these tools in another post.) To make our characters appear and seem “real,” we need to put ourselves in more than their shoes. We need to shape-shift into their bodies.

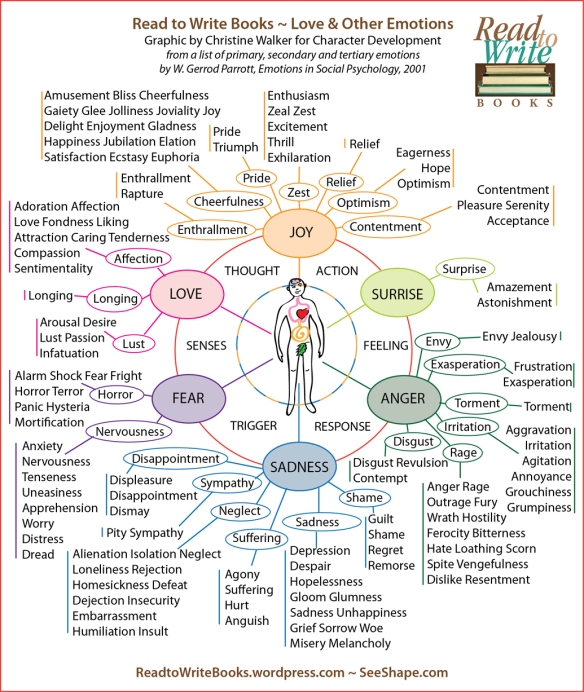

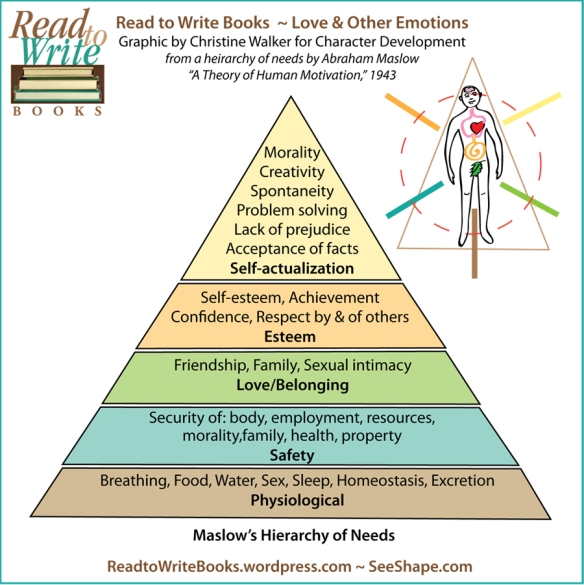

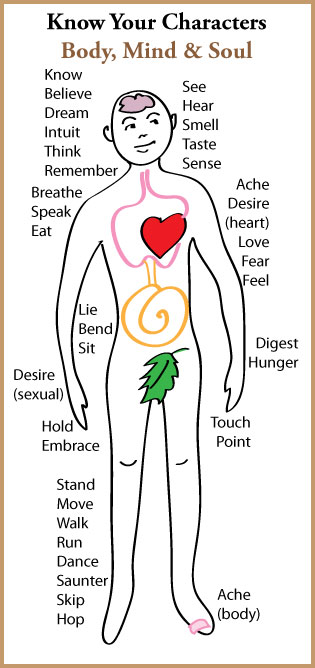

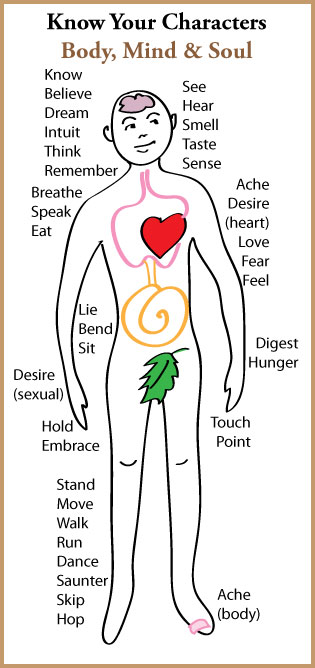

The figure below serves as a nudge to ground our writing in the senses and body of a character. Add your own action verbs and sensory verbs. Keep in mind the three guiding verbs for character-driven fiction: desire, choose, act.

Ground writing in the body and senses

Let’s see how masterful authors do it…

Italo Calvino, Baron in the Trees

Biagio describes Cosimo upon waking: In the morning, on the other hand, when the jackdaw croaked, from the bag would come a pair of clenched fists; the fists rose in the air and were followed by two arms slowly widening and stretching, and in the movement drawing out his yawning face, his shoulders with a gun slung over one and a powderhorn slung over another, his slightly bandy legs (they were beginning to lose their straightness from his habit of always moving on all fours or in a crouch). Out jumped these legs, they stretched too, and so, with a shake of the back and a scratch under his fur jacket, Cosimo, wakeful and fresh as a rose, was ready to begin his day.

Rachel Cusk, The Country Life

Stella, the first-person narrator, suffers: I examined my arms, and to my dismay saw that they were a furious red, cross-hatched with hundreds of thick, raised white lines, as if I had worms embedded beneath my skin. Crying out, I flung back the eiderdown… I scratched, tearing at my nightdress like a maniac, and then understood that I was going to lose control of myself if I continued in this fashion. I sat, hot and exhausted, on the corner of the bed, my head in my hands. My skin tingled and itched now that my fingers were not attending to it. I bridled my urge to scratch, forcing my hands into my mouth. My back felt unbearably hot. Around me the night was shrunken and dense, like the pupil of an eye contracted to a pinprick.

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

Readers (listeners) are in concert with Mrs. Ramsay: But here, as she turned the page, suddenly her search for the picture of a rake or a mowing-machine was interrupted. The gruff murmur, irregularly broken by the taking out f pipes and the putting in of pipes which had kept on assuring her, though she could not hear what was said (as she sat in the window which opened on the terrace), that the men were happily talking; this sound, which had lasted now half and hour and had taken its place soothingly in the scale of sounds pressing on top of her, such as the tap of balls upon bats, the sharp, sudden bark now and then, “How’s that? How’s that?” of the children playing cricket, had ceased; so that the monotonous fall of the waves on the beach, which for the most part beat a measured and soothing tattoo to her thoughts and seemed consolingly to repeat over and over again as she sat with the children the words of some old cradle song, murmured by nature, “I am guarding you—I am your support,” but at other times suddenly and unexpectedly, especially when her mind raised itself slightly from the task actually in hand, had no such kindly meaning, but like a ghostly roll of drums remorselessly beat the measure of life, made one think of the destruction of the island and its engulfment in the sea, and warned her whose day had slipped past in one quick doing after another that was all ephemeral as a rainbow—this sound which had been obscured and concealed under the other sounds suddenly thundered hollow in her ears and made her look up with an impulse of terror.

Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried

The author Tim O’Brien gets inside his character Tim O’Brien: I remember the monotony. Digging foxholes. Slapping mosquitoes. The sun and the heat and the endless paddies. Even in the deep bush, where you could die any number of ways, the war was nakedly and aggressively boring. But it was a strange boredom. It was boredom with a twist, the kind of boredom that caused stomach disorders. You’d be sitting at the top of a high hill, the flat paddies stretching out below, and the day would be calm and hot and utterly vacant, and you’d feel the boredom dripping inside you like a leaky faucet, except it wasn’t water, it was a sort of acid, and with each little droplet you’d feel the stuff eating away at important organs. You’d try to relax. You’d uncurl your fists and let your thoughts go. Well, you’d think, this isn’t so bad. And right then you’d hear gunfire behind you and your nuts would fly up into your throat and you’d be squealing pig squeals. That kind of boredom.

Richard Yates, Doctor Jack-o’-lantern (Eleven Kinds of Loneliness)

Body language reveals Vincent Sabella’s trepidation at being a new kid in class in : He arrived early and sat in the back row — his spine very straight, his ankles crossed precisely under the desk and his hands folded on the very center of its top, as if symmetry might make him less conspicuous — and while the other children were filing in and settling down, he received a long, expressionless stare from each of them.

Whitney Otto, How to Make an American Quilt

An illicit encounter elicits desire and implies what will happen next for Sophia: He presses her flush against the stone wall with his heavy, clothed body. Now he is running his hand along the inside of her thighs, splitting her legs apart, nestling his body between them. Sophia thinks she will lose her breath forever, will drown and not care, will always have this sensation of inner heat and outer cold. He cradles her against the quarry rock. She trembles in his arms. She knows what she will say and without hesitation. Yes.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Clarissa Dalloway begins her day with senses heightened and flows to the reader a spectrum of color and fragrance: Ah yes—so she breathed in the earthy garden sweet smell as she stood talking to Miss Pym who owed her help, and thought her kind, for kind she had been years ago; very kind, but she looked older, this year, turning her head from side to side among the irises and roses and nodding tufts of lilac with her eyes half-closed, snuffing in, after the street uproar, the delicious scent, the exquisite coolness. And then, opening her eyes, how fresh like frilled linen clean from a laundry laid in wicker trays the roses looked; and dark and prim the red carnations, holding their heads up; and all the sweet peas spreading in their bowls, tinged violet, snow white, pale—as if it were the evening and girls in muslin frocks came out to pick sweet peas and roses after the superb summer’s day, with its almost blue-black sky, its delphiniums, its carnations, its arum lilies was over; and it was the moment between six and seven when every flower—roses, carnations, irises, lilac—glows; white, violet, red, deep orange; every flower seems to burn by itself, softly, purely in the misty beds; and how she loved the grey-white moths spinning in and out, over the cherry pie, over the evening primroses!